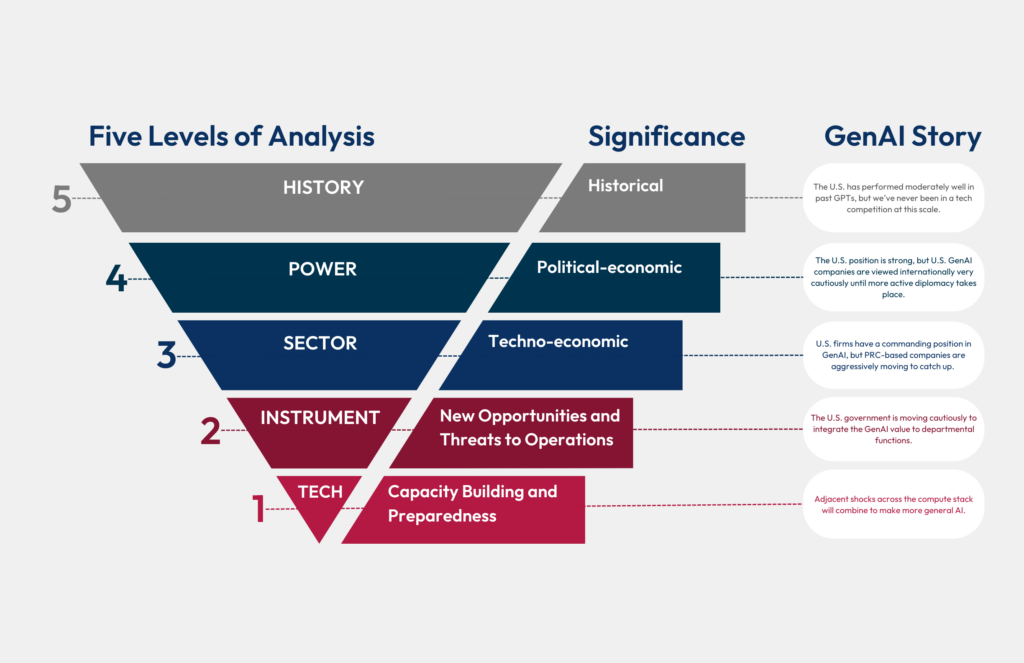

The rapid emergence of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) begs a core question: how will this new general purpose technology impact the full extent of America’s national security institutions? A natural starting point is thinking about GenAI in terms of national power. Constant jockeying with rivals for tech leverage is Positioning School logic as old as war and the notion of the state itself.1 Fundamentally, as SCSP argued in Mid-Decade Challenges to National Competitiveness, a nation is better served by being strong in tech power rather than being weak.2 A nation’s competitive advantages grant it leverage in technology competitions. In a period of international competition, nations should be intentional and selective as to which competitive advantages they invest in and maintain in order to cultivate tech power.

Policymakers need a method for identifying and focusing on the critical variables. An approach with multiple levels of analysis does not inherently yield a strategy, but it grants more command over the factors and nuances of tech power that a nation can harness.3 Then, given that foundation, policymakers can combine different facets of tech power to build a real strategy.

“An approach with multiple levels of analysis …grants more command over the factors and nuances of tech power that a nation can harness.”

For GenAI, considering five levels of analysis would help policymakers grasp this technology’s impacts on national security and provide a starting point for how to organize for this era. These start from a technology level and move to a more macro, historical level of thinking. Each level can stand alone, providing a framing in its own right. Yet simultaneously, adroit policymakers will recognize that employing all five levels cumulatively, each building out of the previous one, will offer a more comprehensive assessment.

The Tech Level

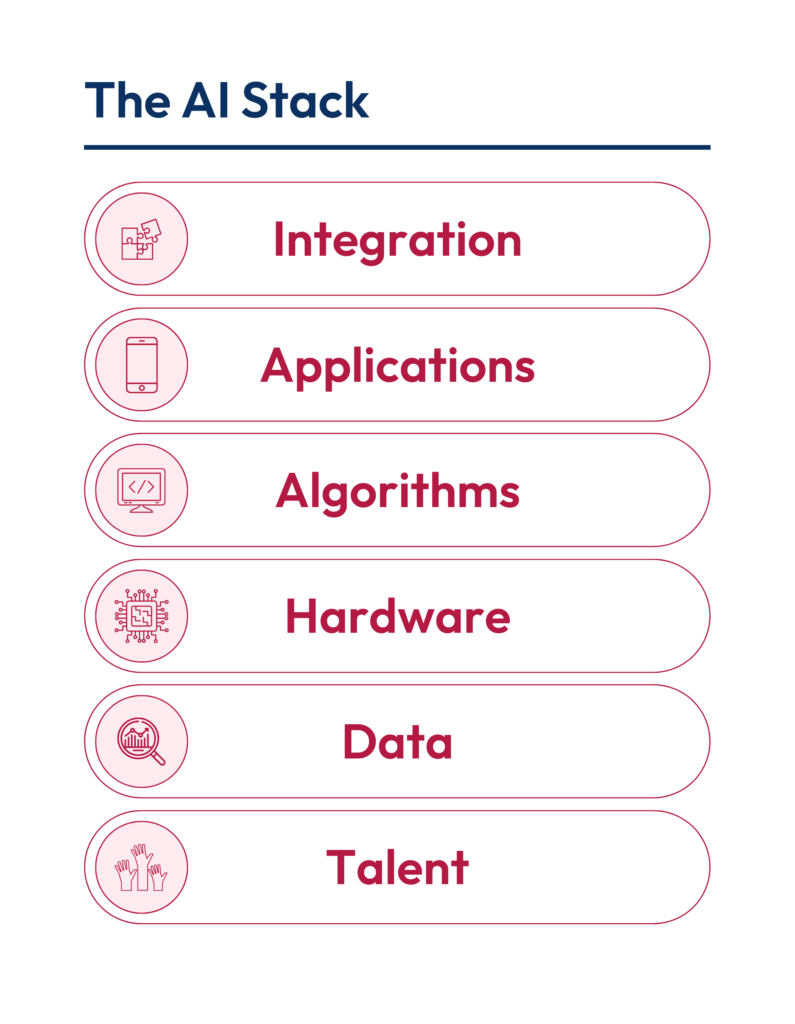

The Tech Level surveys a technology’s elements, or “stack,” that make the tech actually work.4 This level dives into how the tech actually works and then explores if a government or organization is organized to leverage its power. It is a way to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the INPUTS to the development of a technology. Understanding the strengths and weaknesses of these inputs enables projections of where and how fast the technology is headed, and what adjacent shocks could supercharge or upset the trajectory. It also clarifies what essential inputs or supply chains are necessary for the tech to function.

As an example, the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence’s (NSCAI) breakdown of AI into hardware (compute), data, algorithms, applications, integration into real-world operations, and talent goes behind the curtain into how AI functions.

Understanding these foundational elements will position policymakers to adapt to future developments as GenAI continues to evolve across the entire stack. From data “auto-labeling”5 to algorithmic “pruning”6 and human-machine “co-piloting,”7 additional advances will continue to upend existing assumptions, offering new possibilities. The tech level of analysis helps policymakers ground themselves to form a more adaptable strategy that can leverage an ever-evolving GenAI suite of tools.

The Instrument Level

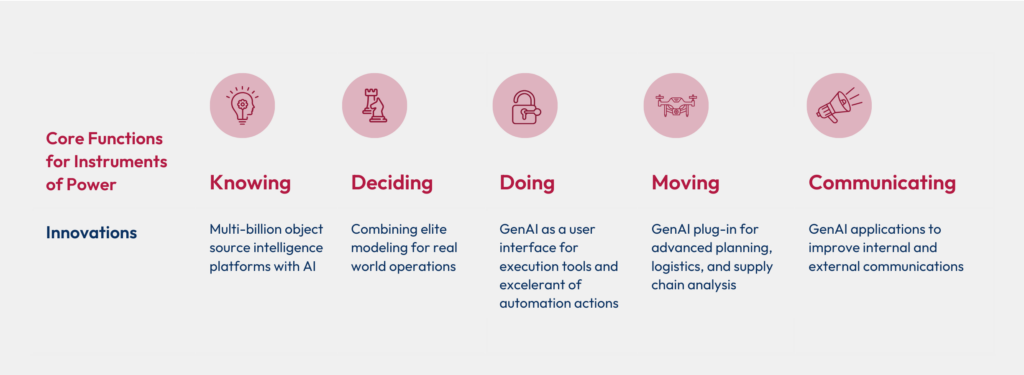

The Instrument Level considers how the technology will be used by the organizations that have access to the technology. The instrument level is the first step in understanding the output or impact that a technology creates. In the United States there are four basic instruments of state power — diplomatic, informational, military, and economic.8 However, competitors may think about state power differently. For example, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) may consider the internal security aspects of state power and the external subversion aspects differently from the way the United States does. Though, in both cases, this would be part of the informational instrument. The central question under this level is: how will this technology change the landscape of departments and agencies in which these instruments operate and the functions to which the specific technology is applied?

GenAI holds the potential to reshape the landscape in which these instruments function. An AI-enhanced world alters how nations conduct diplomacy to prevent conflict or strategic communications amidst AI-generated content; and, as the October 7, 2022 export controls9 clearly demonstrate, emerging AI tools can shift the use and priorities of long-standing instruments of economic statecraft.

Across all instruments of statecraft, private sector AI innovations are transforming the core functions of how instruments work, providing the potential to master that new environment if embraced and adopted. As such, each department or agency that wields these instruments of state power must also understand how to graft new GenAI tools into these existing functions. Absent such integration, these departments and agencies will struggle to operate effectively and with impact in a GenAI world. Most basically, every department or agency must take in information and proactively, or reactively, make decisions. GenAI models can help — analyzing massive quantities of real world, open-source data or providing novel recommendations. Likewise, as departments coordinate assets or move personnel and resources, new GenAI communications and logistics tools will facilitate faster and more accurate operations. Finally, GenAI can support more efficient and bespoke external strategic communications with policymakers both at home and abroad as well as with the wider public.

Core functions for instruments of power, paired with private sector innovations, could improve performance of each function and thus, the overall instrument of power.

The Sector Level

The Sector Level analyzes the impact of the technology on the overarching techno-economic competition by examining the intersection and interaction of strategic technology sectors at the competition’s core.10 As much as individual technological advances yield benefits in their own right, it is often at the junctures of multiple technologies that the greatest range of benefits and new opportunities emerge. Technologies will have different outputs and impacts depending on how they can be integrated into and reshape other technological and functional sectors. Some actors compartmentalize new technologies (e.g. the Soviet Union and compute technologies).11 Others resist or over regulate the disruptive effects of new technologies.12 Therefore, assessing GenAI, and AI in general, in tandem with other strategic technology sectors as a whole sheds light on the nation’s broader techno-economic prowess.

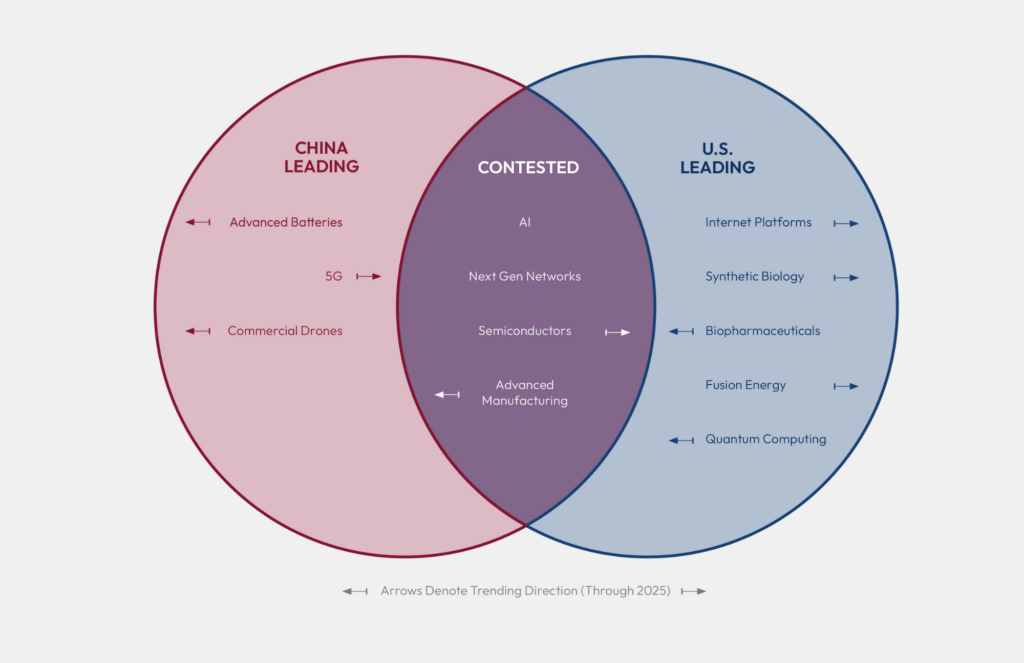

Under the sector level, the PRC’s overall ecosystem is producing real tech advantages. With respect to GenAI, the U.S. ecosystem enjoys a momentary lead. American actors likely will be able to harness that edge, deploying GenAI tools in other emerging technology sectors, like biotechnology, to deliver original, fast-paced breakthroughs.13 However, the United States cannot afford to sit on its laurels. The PRC remains a powerful player in AI writ large, as well as in several other strategic technology sectors where the deployment of AI tools could yield real results. Between those existing advantages, robust PRC-based talent, and Chinese Communist Part (CCP) top-down emphasis and resourcing, the PRC could move rapidly to catch up, helping tip the balance in a number of other strategic sectors.

The Power Level

The Power Level considers how a technology will be used by the national government for the purpose of achieving its external objectives. The power level examines the capabilities identified via the instrument and sector lenses and how they can be deployed in pursuit of policy goals. The power level of analysis considers the advantages found under the sector level and, like a general, deploys those advantages upon a map to see how they would deliver influence in the physical world. Governments, private firms, and individual consumers all seek access to various technologies that shape the world in which they live and operate, providing the technology provider with influence. That influence easily spills across domains, as economic factors, such as port ownership, extend into military domains, such as which nations can reliably access that port.14 However, different national governments may have different strengths and weaknesses in using the available technology.

For example, on GenAI, the U.S. private companies charging forward with the best LLMs grant the United States a certain international prestige that translates to influence but the U.S. government may face constraints in using private sector models.15 The PRC may not face the same constraints. As GenAI tools increasingly combine with other tech and economic sectors, vectors to expand that influence will grow. As the PRC has made considerable strides through efforts like the Belt and Road Initiative16 and Digital Silk Road,17 the United States should seek to consolidate and build on its early AI gains and consider how to transfer that value to reinforce national security goals, foremost through steps outlined later in this report.

PRC Technology Spheres of Influence show how tech power is cumulative across seven categories of tech influence.18

The Historical Level

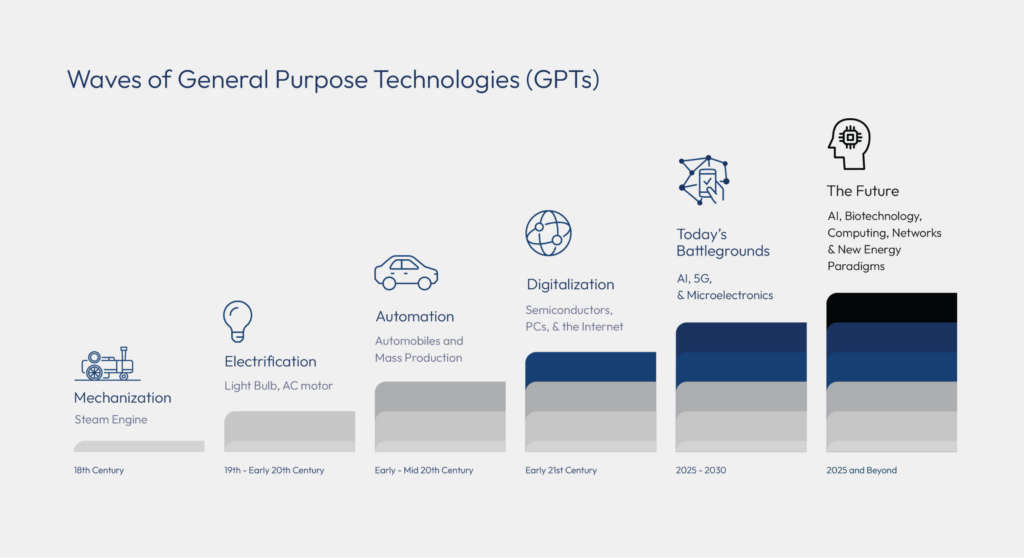

The Historical Level studies the most sweeping question of how technology impacts the trajectory of human history. The question at this broadest level is: how can a nation position itself to be on the right side of history with this technology? This requires an assessment of the goals and values of the nation that is developing this technology and harnessing its power to advance its values and interests. Relative tech power between nations ebb and flow over decades. Thus, the historical level of analysis looks beyond momentary positional advantages to long-term trajectories that lend grand strategy the perspective of time. There are eras in human history when technologies, or combinations of technologies, allow actors to change the world. 16th century nautical tools opened an age of global exploration. Together, electricity and mechanization yielded the Industrial Revolution. The further convergence of mechanization and electrification with the computer led to today’s cyber domain, where information is instantly accessible on a global scale.19 These technologies fundamentally transformed the way humans live, work, and communicate. Today we appear on the cusp of another such transformation.

GenAI, much like electricity, is positioned to be a general purpose technology that affects most aspects of our economy, our society, and our daily lives. At the historical level, one can better see the potential sweeping significance of GenAI. LLMs have ushered in the beginning of AI that is truly and broadly useful to anyone with an internet connection and GenAI is already combining with other sectors to yield original and faster discovery and innovation. This convergence is likely to drive technology history in the coming years.

This chart shows the march of general purpose technologies going back to the machine age. Mechanization, electrification, automation, digitization, AI, and biotech are combining and stacking upon each other over time.20

GenAI has opened the door to a new era. The pace of change is rapid. Using these preceding lenses, policymakers can orient themselves on these shifting sands to strategize and organize for action. Absent such efforts, others will fill that space, and our future will be left to chance.

Endnotes

- On the Positioning School, see Henry Mintzberg, et al., Strategy Safari, Prentice Hall at 85 (2009).

- Mid-Decade Challenges to National Competitiveness, Special Competitive Studies Project at 16-27 (2022).

- Pressing questions of grand strategy and international relations have often been addressed by a framework that incorporates multiple lenses to view complex security studies questions. See Kenneth Waltz, Man, the State, and War, Columbia University Press (2018); Steve Yetiv, Explaining Foreign Policy, Johns Hopkins University Press (2011); Graham Allison & Philip Zelikow, Essence of Decision, Longman (1999).

- The notion of the “compute stack” builds on that of the “AI stack” found in the Final Report of the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence. See Final Report, National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence at 31-32 (2021).

- See Nikolaj Buhk, How to Automate Data Labeling, Encord (2023).

- See Mark Kurtz, What is Pruning in Machine Learning?, Open Data Science Community (2020).

- See Ian Sherr, et al., AI as Co-Pilot: Your Online Life Is About to Change, Like It or Not, CNET (2023).

- Power models come in many forms. These examples follow the DIME model, which recognizes the four instruments of national power as diplomatic, informational, military, and economic. See Jack Kiesler, A Next Generation National Information Operations Strategy and Architecture, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at 4 (2021). National tech power subtending these four instruments could yield a DIME-T model. Some Chinese scholars have built on Joseph Nye’s hard/soft power distinction to model “comprehensive national power” that includes aspects such as a country’s science and technology capacity, natural resources, educational system, and more. See Huang Shuofeng, New Theory on Overall National Strength (1999); Ryan Hass, From Strategic Reassurance to Running Over Roadblocks: A Review of Xi Jinping’s Foreign Policy Record, China Leadership Monitor at 10 (2022).

- Press Release, Commerce Implements New Export Controls on Advanced Computing and Semiconductor Manufacturing Items to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Bureau of Industry and Security, U.S. Department of Commerce (2022); Ana Swanson, Biden Administration Clamps Down on China’s Access to Chip Technology, New York Times (2022).

- On selecting those strategic technology sectors, see Harnessing the New Geometry of Innovation, Special Competitive Studies Project at 33-36 (2022).

- Chris Miller, Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, Scribner at 35-39 (2022).

- For the historical example of Ming China, see Orville Schell, A Ming Emperor Would Have Grounded the Shuttle. Bad Idea, Washington Post (2003).

- Eric Schmidt, This is How AI Will Transform the Way Science Gets Done, MIT Tech Review (2023).

- For one case study on how tech choices can have impacts on geopolitical calculations, see U.S. surveillance concerns regarding a PRC-based company building and installing equipment in the Israeli port of Haifa. Danny Zaken, Chinese-operated Port Opens in Israel Despite American Concerns, Al Monitor (2021); Arie Egozi, US Presses Israel On Haifa Port Amid China Espionage Concerns: Sources, Breaking Defense (2021).

- Generative AI: A New Moment for American Leadership in the Indo-Pacific?, Special Competitive Studies Project (2023).

- James McBride, et al., China’s Massive Belt and Road Initiative, Council on Foreign Relations (2023).

- See Assessing China’s Digital Silk Road Initiative, Council on Foreign Relations (2023).

- Harnessing the New Geometry of Innovation, Special Competitive Studies Project at 10-14 (2022).

- Don Tapscott & Anthony Williams, Wikinomics: How Mass Collaboration Changes Everything, Portfolio at 12 (2006).

- Mid-Decade Challenges to National Competitiveness, Special Competitive Studies Project at 171 (2022).