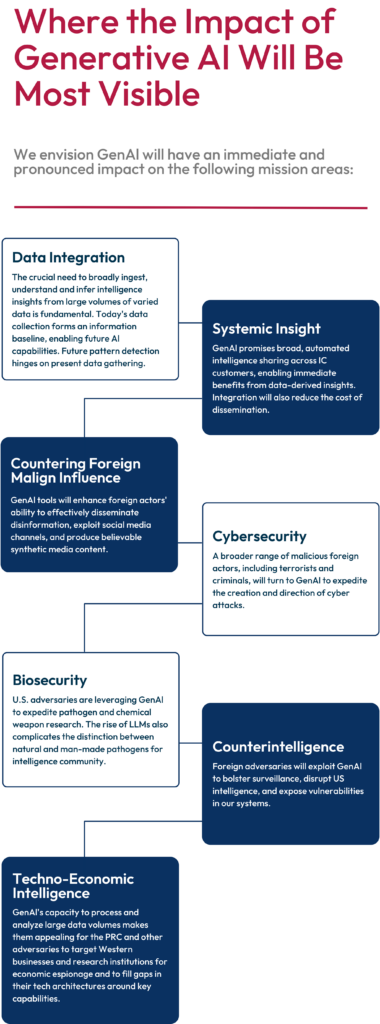

Recent rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have made it clear we are on the threshold of the next era of intelligence, one that will be defined by how well intelligence services leverage AI tools to collect, sift, and analyze global data flows to generate insight and deliver effects. The U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) should take immediate action to leverage these emerging capabilities to protect the nation and maintain our competitive advantage over the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The IC has traditionally been at the cutting edge of adopting emerging technology but, unlike earlier technological leaps that were mostly additive in nature, generative AI (GenAI) will not only transform how intelligence work is done but also enable intelligence services to accomplish far more than they can today.

The IC has already taken advantage of earlier forms of AI and is using machine learning (ML) and natural language processing (NLP) tools to help it manage the exponential increase in data that has overwhelmed collectors and analysts in recent years.1 GenAI will have an even broader impact. As Large Language Models (LLMs) – multi-modal models that can generate images, video, and sound, and other forms of GenAI become more numerous, faster, more accurate, and more capable – IC agencies will come under strong pressure to adapt their approaches to every portion of the intelligence cycle, from planning and collection to analysis and dissemination.

Without question, the spread of GenAI will further complicate the IC’s already complex mission. For the United States’ adversaries, GenAI will provide them new avenues to penetrate its defenses, spread disinformation, and undermine the IC’s ability to accurately perceive their intentions and capabilities. More broadly, GenAI will further democratize intelligence capabilities, enabling more actors to swim in the ocean of global data in pursuit of their own goals. Just as the IC currently tracks foreign leaders and institutions, intelligence services will eventually need to plan and account for AI-enabled machines acting as semi-independent actors, directing operations and making decisions, both for our adversaries and allies.

The effects of GenAI will not stop there. As AI tools become more prevalent and mature, they will put additional strain on several long-held IC practices and cultural norms, such as the relative importance of classified over unclassified data sources, legal restrictions against the use of data sources that might contain privacy and proprietary information, and what it means for something to be “secret” or “clandestine” in a global, hyper-connected, digital datasphere. Relying on unique, sensitive, and often expensive sources and methods to uncover secrets will no doubt remain a core component of what the IC does in the future. But the utility of traditional intelligence collection will increasingly be measured against what can be obtained from publicly and commercially available sources that are processed and analyzed by AI acting in partnership with humans.

Despite these challenges, developing an AI action plan for the IC deserves leadership’s urgent attention for two reasons. For one, the speed with which generative AI is evolving is staggering. OpenAI released the first version of ChatGPT in November 2022; it released GPT-4 in March 2023, and newer versions with much greater capability are due by the end of 2023.2 In a clear indication that the global race is on to master this new domain, private industry has already responded by directing over $14.43 billion toward generative AI tools in 2023 compared to $1.57 in 2020.3 Economists at Goldman Sachs estimate that eventually nearly two-thirds of jobs that now exist will be changed by AI in some manner.4 Even more concerning is the prospect of autocratic nations gaining a technological lead that would be extraordinarily difficult for the United States to match, let alone surpass.5 This could leave the country vulnerable to losing the tech competition with the PRC and eventually relegate U.S. intelligence services to obsolescence as they will not be equipped to handle the data environment of the future.

Visualizing the Potential

With the appropriate governance controls in place and support from sufficient infrastructure, the rewards for moving quickly to embrace the potential of GenAI are numerous. Fully deployed LLMs would enhance the IC’s performance in every stage of the intelligence cycle and enable it to cover more issues, and at greater depth.

| Tasks | New Capabilities Enabled by GenAI | |

| Collection Tasks | Planning | Create and disseminate updated and validated tasking requirements to appropriate collectors, identifying and elucidating opportunities for prioritization and deconfliction. Continuously refine collection requirements based on new analytical findings and policymaker requests. Provide collectors with rapid, integrated feedback on reporting from assets and sources for validation purposes and to spot potential CI threats. |

| Targeting & Exploitation | Simulate ‘what-if’ scenarios to reveal novel collection vectors and devise effective tactics. Automate comprehensive patterns-of-life analyses, identifying anomalies and assessing potential risks presented by evolving threats. Fuse intelligence from multiple INTs for joint target insights. Identify and analyze anomalies in large multi-domain datasets. | |

| Counterintelligence & Security | Leverage AI for continuous encryption and decryption of intercepted signals. Embed threat intelligence into workflows, proactively blocking malicious entities. Map adversaries ubiquitous technical surveillance networks. Monitor employees and contractors to detect unauthorized or potential insider threats. | |

| Reports & Production | Taking intelligence outputs and making them rapidly available to their intended audience, either as a direct intelligence product or as a resource for AI-powered queryable technologies, such as heads-up displays (HUDs). Identify and label manipulated and synthetic content across various formats (e.g., text, images, videos, audios) to ensure data authenticity. | |

| Analytic Tasks | Scanning, Monitor & Query Data | Automate alerts for new key data. Revise draft assessments dynamically based on new reports. Enrich datasets using AI-generated synthetic data. Fuse various types of information (text, image, audio) to efficiently and effectively “connect dots.” Triage information flow, prioritizing the most relevant, authoritative sources. Identify and label manipulated and synthetic content. Leverage inductive dependency parsing to understand public opinion and potential societal shifts. |

| Bolstering Analytic Rigor | Simulate causality between data points or events. Create simulations for preparedness and outcome prediction. Use past data to forecast future trends and threats. | |

| Building Substantive & Tradecraft Expertise | Rapidly ingest past production for periodic Analytic Line Reviews.Maintain a Library of Past Production and outside readings for tacit knowledge transfer on analytic accounts.Apply structured analytic techniques to data. Formulate key intelligence questions from data and feedback. Ideate hypotheses based on data and new requirements. Assess performance and tradecraft skills. | |

| Producing Analytic Assessments & Support Customers | Produce first drafts of written assessments. Flag upcoming meetings, visits, and requests by U.S. officials. Automate responses to basic policymaker inquiries. Monitor and evaluate analytic input from liaison partners. |

More fundamentally, the advent of GenAI offers the opportunity to galvanize the Intelligence Community to embrace the broader cultural changes necessary to ensure its success in the digital era. Dubbed by some as the “revolution in intelligence affairs,”6 these cultural shifts include a willingness to use AI and other autonomous systems to process huge volumes of data, reconsideration of the bureaucratic stovepipes separating the different INTs and stages of the traditional intelligence cycle, a greater openness toward the private sector (especially the sources of cutting-edge technology), and even a reconsideration of what constitutes “secret” information.

At the heart of this transformation should be open source intelligence (OSINT).7 Unlocking the power of OSINT should up-end traditional models for intelligence collection and analysis that focused almost exclusively on the IC’s unique, exquisite, and highly-classified intelligence sources and methods. Unlocking secrets will always be an important IC task, but what will matter more in a future high-speed, data-driven tech competition with the PRC will be speed-to-insight, obtained from whatever sources are available. Most of those sources will be openly or commercially available, and the new AI tools to exploit this data will already be trained on much of it. The IC should emphasize greater use of OSINT, making it the INT of first recourse rather than the last. Deploying GenAI tools would enable the IC to do this at speed and at scale, comparatively cheaply, and at lower risk to sensitive sources. Adopting this mindset would put the IC in a better position to keep pace with what industry vendors and academic institutions will be providing U.S. policymakers, and allow it to husband its resources and fragile sensitive capabilities and target them against only the most difficult of targets.

AI and Disinformation: A Critical Near-Term Challenge

Generative AI will magnify the threat of disinformation and foreign malign influence. As more foreign adversaries, criminal gangs, and online trolls lay their hands on GenAI capabilities, they will be able to create disinformation in greater volumes, cheaper, at greater speed, and they will be able to deliver their message payloads with greater precision and with more stealth than ever before. The democratization of these tools lowers the barrier to entry for malign actors and will enable them to generate deepfake images, synthetic audio, and text that is nearly indistinguishable from other content.

The pro-CCP influence operation “Spamouflage” illustrates the new danger. First identified in 2019,8 “Spamouflage” has progressively incorporated AI, starting with AI-generated fake avatars in 2020.9 This year US industry revealed that the group was promulgating fully-synthetic videos that contained fake content. The “Spamouflage” operators embedded AI-generated video clips of fictitious news anchors from the fictitious “Wolf News” into their network that appeared incredibly life-like and initially fooled experts before deeper technical analysis revealed them as fakes. In the videos, the voiceovers promoted ideas in line with CCP interests, such as accusing “the U.S. government of attempting to tackle gun violence through ‘hypocritical repetition of empty rhetoric’” and stressing “the importance of China-U.S. cooperation for the recovery of the global economy.”10 While none of the videos received more than 300 views11 between November 2022 and their exposure in February 2023,12 they were the first incident of wholly AI-generated videos (as opposed to AI edited). In August 2023, Meta announced its largest takedown to date of the same Spamouflage network with 7,704 Facebook accounts, 954 Pages, 15 Groups and 15 Instagram accounts.13

The IC should devote more resources and attention toward revealing and understanding foreign malign influence operations that use GenAI tools and provide US law enforcement, homeland defense organizations, and election security officials with more timely and actionable Indications & Warnings (I&W) intelligence support. GenAI will also provide new opportunities to mitigate disinformation threats. Newly-developed AI classifiers14 and detection algorithms could help the IC identify synthetic media. Similar to the work being done by entities abroad, the IC could employ various AI models to run similarity analysis across suspected disinformation to identify narratives and cross-reference them with known, or suspected, troll activity.15 Alongside the use of GenAI, existing efforts inside and outside the U.S. government to mark synthetic data via digital watermarking,16 content provenance,17 and blockchain immutable ledgers18 could further enhance IC capabilities. Natural Language Processing technologies also present the opportunity to automatically run sentiment analysis at speed across the worlds’ media outlets and social media platforms to quickly identify trends in malign influence campaigns and assess their impact on foreign opinion.

Actions the IC Should Be Taking Now

To fully capitalize on GenAI’s potential, the IC must quickly move beyond experimentation and limited pilot programs to begin deploying GenAI tools at scale. Speed is essential. IC agencies should make it a priority to incorporate and begin using enterprise-level generative AI tools within the next two years. This is an ambitious goal, but it is achievable and essential if the IC is to stay relevant. It will require the IC – with the support of the White House and Congress – to make some critical decisions about how the IC will utilize GenAI, particularly whether to build its own in-house models or leverage commercially-developed models, the extent to which it builds unified or federated GenAI systems across the IC, and what standard will govern the IC’s use of AI. While all these issues are important to getting AI right across the IC, it will take time and further experience working with GenAI to resolve them. This should not stand in the way of the IC making progress now toward implementation.

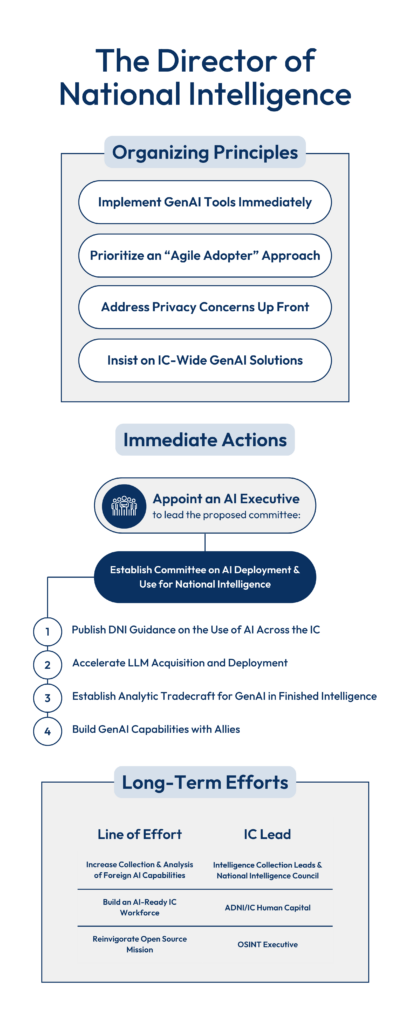

To ensure alignment across the IC, the DNI should insist that IC agencies adhere to four critical principles regarding AI implementation:

- Begin Using GenAI Tools Immediately. Because GenAI will have such a profound impact on how IC professionals will go about their work, it is vital that the IC begins to make broader use of these tools immediately so that it can train its workforce and begin to create the infrastructure and policies it will need to employ LLMs safely and effectively. In part to help the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) respond to Congressional requirements for updates, ODNI should require IC agencies participate in a new IC-wide AI Governance Committee (see below) and demonstrate how they are contributing to or using IC-wide GenAI architectures, and/or developing their own enterprise solutions.

- Focus on Being an “Agile Adopter.” IC agencies are being pressed to choose between two extreme approaches when thinking about how to deploy LLMs and multi-modal models: 1) opt to do very little in-house development and instead rely on commercially-provided models for limited purposes, or 2) invest large sums of money to build state-of-the-art models at IC owned-and-operated facilities that utilize OSINT in addition to IC data holdings and seek to match the latest generations of commercial systems. However, there is a more balanced alternative. The IC should partner with a leading foundation model provider to acquire their LLM. Then, modify it to incorporate IC-owned datasets and unique terminology, or pair it with a smaller, IC-developed model. Given that many of the ‘largest’ LLMs do not disclose their training datasets, the IC should advance efforts by the General Services Administration (GSA)19 to establish independent standards or rating systems for evaluating the datasets used in training (as described in the text box below). This strategy would offer an effective method for assessing the resulting model’s efficacy, promoting greater transparency and trust in the application of these models.

- Tackle Privacy Concerns Up Front. By their nature, LLMs – particularly so-called frontier models – include anonymized data from across the Internet, to include data on U.S. persons, for training purposes. ODNI should work on getting IC agencies the necessary authorization to make use of LLMs that include personal identifiable information (PII). This may require exemptions to existing PII20 restrictions, or it may require creative partnership with another agency – such as the GSA – that is authorized to manage LLMs21 on behalf of the U.S. government. Left unresolved, IC agencies are likely to take a varied approach, with some embracing LLMs and others severely restricting their use. In addition, this will open opportunities for adversaries to “poison” LLMs with privacy or protected intellectual property data to prevent IC use.

- Insist on IC-Wide AI Solutions Wherever Possible. The IC will need to strike the right balance between fostering a climate of innovation to encourage AI development across the 18 agencies and establishing coordinated approaches to achieve economies of scale. AI expertise varies across the Intelligence Community and there will be a tendency for agencies to protect their unique datasets and capabilities. Left unaddressed, this could result in a proliferation of small LLMs that individually and collectively will pale in comparison to what will be used by the PRC or that will be commercially available. And the IC would achieve none of the economies of scale or uniform governance standards possible. ODNI’s just-published 2023-25 Data Strategy should serve as the model for aligning IC agencies on AI strategy.22 ODNI should use its budget authority to insist that the major IC players – CIA, NSA, NGA, and DIA – cooperate to acquire near-cutting-edge LLMs from the private sector to train on their data holdings, and it should exercise its convening authority to bring the Intelligence Community together to set standards for AI use. As the IC’s LLM capabilities mature, there ought to be flexibility for some agencies to tailor their stand-alone, smaller models for specific purposes aimed at protecting sensitive sources and methods. As long as such models are the exception, not the rule, then they will add to AI’s impact without inhibiting overall IC performance.

Desirable Characteristics for IC Large Language Models. As IC agencies consider which LLMs to license, test, build or deploy, they should require them to fulfill at least the following criteria:

– Accessible to cleared researchers, analysts, and operators for inspection and instrumentation throughout the model development and deployment lifecycle.

– Able to ingest structured and unstructured live data from various IC elements, irrespective of location (e.g., multi-cloud, hybrid, prem), modality (e.g., text, image, audio, video), or classification level (e.g., unclassified, confidential, secret, top-secret).

– Secured from revealing sensitive information, including classified data, tradecraft methods, and the content of prompts and outputs.

– Minimize the risk of being trained on sensitive data, especially proprietary23 or privacy information.24

– Adheres to analytic and operational standards, generating accurate and relevant insights with sources that are credible and verifiable, with minimal hallucinations.

With these broad goals in mind, we recommend that the DNI appoint a senior IC lead for AI implementation. That officer should report directly to the DNI, have the appropriate expertise and skills to lead the IC’s AI efforts, and be given authority over agencies’ AI budgets and implementation. The AI Lead should convene a panel of AI program managers, IT security experts, and acquisition officials from across the Intelligence Community to begin making decisions on LLM acquisition, governance, and use. This IC Committee on AI Deployment and Use should be the body that advises the DNI on which direction to take on matters pertaining to creating common IC architectures (datasets and AI algorithms), security and counterintelligence requirements, setting standards for analysts, collectors, and others to use AI tools, and establishing guardrails for the protection of privacy information and intellectual property. The AI Committee should be appropriately resourced and empowered to complete the following tasks within six months:

- Publish DNI Guidance on the Use of AI Across the IC. The Committee should produce an Intelligence Community Directive (ICD) by March 1, 2024, that defines and establishes the parameters that will govern the IC’s use of LLMs and other AI tools.25 Among other objectives, the new ICD should define acceptable IC uses for generative ICD tools and provide exemptions for using private data on U.S. citizens, consistent with the guidelines established by ODNI’s Chief for Civil Liberties, Privacy, and Transparency.26

- Identify Steps to Remove the Obstacles to Faster Acquisition and Deployment of LLMs. Leveraging GenAI necessitates faster technology acquisition and absorption. ODNI should exercise its full authority to shorten procurement timelines for critical emergency technologies related to LLMs. This includes finding ways to move faster in the context of the Federal government’s annual budget and appropriations cycle. The IC, for example, could do so by encouraging IC element Directors, Deputy Directors, and Senior Acquisition Executives (SAE) to use Other Transaction Authority (OTA) and Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO) authorities to pursue non-standard procurement and innovative commercial capabilities or technological advances at fixed price contracts of up to $100 million, respectively.27 To facilitate the adoption of AI technologies, ODNI should require greater transparency across elements to understand the GenAI technology acquisition environment. The status of various efforts could be consolidated into a single platform, allowing the DNI and agency leaders to identify opportunities for collaboration and places where they should amend IC acquisition authorities to increase the speed of technology adoption.

- Establish Analytic Tradecraft Standards for the Use of Generative AI for Finished Intelligence. The recommended IC Committee on AI Deployment and Use, in coordination with the National Intelligence Board that includes the heads of analysis from each IC agency, should articulate common standards and concepts to measure the efficacy of novel analyses produced by humans in collaboration with generative models. The Committee’s findings should be integrated into strategic planning and budget documents, and incorporated into existing analytic tradecraft standards, including ICD 203.28 Meanwhile, the DNI should incentivize analytic units across the IC to experiment with LLMs by directing relevant IC leaders to: 1) deploy OSINT-trained LLMs to analysts’ computers, 2) work with the Office of Human Capital and the IC Training Council to update intelligence training to prepare all personnel for continuous machine collaboration in their careers, and 3) grant National Intelligence Program (NIP) Managers and Military Intelligence Program (MIP) Component Managers the freedom and resources necessary to accelerate HMT at the analyst level.

- Design AI Capabilities with Allies From the Start. The Committee should plan now on how the IC will enable and empower friendly liaison services to also leverage GenAI capabilities to prevail in a long-term techno-economic contest with the PRC. Many U.S. partners such as the United Kingdom,29 Israel,30 the United Arab Emirates,31 and Japan,32 are already fostering private sector development and government use of AI-enabled tools; others are farther behind. In concert with the DNI, the Directors of CIA, NSA, and DIA should convene a consortium of AI-proficient allied states to share best practices and establish common use guidelines and principles. This consortium should broaden AI-related technical collaboration to develop shared tools. It could also be undertaken within the AUKUS Pillar II framework and ongoing AUKUS Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy working group.33 Other possibilities include forums like the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue’s Critical and Emerging Technology Working Group.34 Because the United States is a leader in AI, such an approach would position America to help set standards for global intelligence services’ use of GenAI that ensure U.S. citizens’ privacy and U.S. industries’ interests are better protected.

Longer-Term Efforts

These measures are the minimum necessary to start making progress toward deploying LLMs and stay ahead of the PRC, but they will not be enough to sustain the IC’s leadership. Additional reforms to the IC’s approach to workforce recruitment and development and how it leverages open source intelligence will be necessary to maintain the intelligence advantage in AI. Specifically, the IC should focus on:

Increasing Collection and Analysis on Foreign AI Capabilities. It is essential that the IC provide U.S. policymakers with accurate information and analysis on how foreign adversaries and competitors – particularly the PRC – are progressing in their development and deployment of GenAI tools, and how they intend to use them against us. The DNI should task collectors to devote more resources to obtaining non-public insights into foreign AI plans, and this may require a tighter lashup between HUMINT and technical collection experts and the IC’s analytic experts on AI to better refine the IC’s targeting. The DNI also should task the National Intelligence Council (NIC) to assemble a network of IC all-source analytic experts to assess foreign development and use of LLMs and other GenAI tools. IC analysts should regularly evaluate foreign GenAI models and their potential utility for disinformation, weapons development, counterintelligence, and other harmful uses. The NIC should organize a cross-IC Red Team to also consider how the PRC or other adversaries would seek to forestall, or undermine, the U.S. government’s use of LLMs and to augment their ability to conduct cyberattacks against our infrastructure and ramp up their disinformation operations targeting U.S. citizens. The NIC AI Red Team should present its findings to the White House and Congressional oversight committees by January 1, 2024.

Building an AI-Ready IC Workforce. The key to harnessing GenAI’s potential for securing an intelligence edge resides in the IC’s people — from the developer to the end-user. The IC cannot afford to “buy” external expertise. To stay abreast of the fast-paced advancements in GenAI and related technologies, the IC must attract the right talent while also sharpening the digital acumen of its existing cadre of intelligence professionals. The DNI should delegate the ADNI/IC Human Capital to undertake three key measures:

- Establish a universal “AI technical competence” standard for intelligence elements. These should incorporate new and existing AI skills defined by the Office of Personnel Management (OPM).35 The DNI should also update and harmonize directives36 with workforce strategies and existing technology-centric talent exchange programs such as the IC’s Intelligence Learning Network,37 Civilian Joint Duty Program,38 and the Public-Private Talent Exchange.39

- Build official career tracks for GenAI tech talent across the IC. In coordination with the OPM and the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), the IC should develop one or more occupational series, associated policies, and official position titles related to GenAI and digital career fields.40 Descriptive parenthetical titles should be introduced to accurately identify IC software professionals in the short-term.41 This immediate step will assist IC talent management strategies for attracting and retaining GenAI tech talent.

- Revamp analytic incentives. The rise of GenAI will transform how analysts go about their work. New tools will enable analysts to contend with the mountains of data available, but human experts will need to adjust their approach and learn to partner with machines to be successful. Rather than spending their time painstakingly searching through reports to find relevant data, analysts increasingly will oversee AI Agents — autonomous software skilled at web navigation, information validation and disinformation detection, and keeping track of ever-evolving customer requirements — to discover new information and discern when the data support alerting customers to potentially valuable new insights.42 This will require a different, more proactive mindset to manage these networks of virtual AI Agents on the one hand, and an increased willingness to trust in what these Agents are saying is new, important, or otherwise relevant to policy consumers.43 To ease this shift, the IC must revamp its training initiatives, equipping analysts with the essential skills and tools to handle GenAI-centric tasks, including guiding AI Agents towards making better discoveries.

- Leverage American expertise in GenAI as a national resource for IC competitive advantage. The IC should encourage technical experts leaving the IC to join the National Intelligence Reserve Corp (NIRC),44 while simultaneously establishing new volunteer avenues for private sector technology specialists to become part of the NIRC, effectively serving as a “digital reserve force.”45

Reinvigorating the Open Source Mission. To get the best use out of LLMs, particularly foundation models that are trained on vast amounts of OSINT data, the IC needs to dramatically increase its access and use of OSINT of all kinds, including commercially available information. As a first step, ODNI should empower the new position of OSINT Executive to harmonize the use of OSINT across the enterprise and to identify successful programs and advocate for them to receive greater resources. But this step alone is unlikely to overcome IC agencies’ reluctance to make OSINT a priority or deliver the variety or quality of OSINT information required. ODNI should also begin exploring alternative solutions, including the possible creation of a new Open Source Agency (either within the IC or outside of it) or creating a new public-private partnership with industry to gain greater access to the private sector’s growing capabilities.

Endnotes

- Since the 1980s, US intelligence has recognized AI’s potential for efficient data management. However, experiences with AI have been inconsistent and modest at best, delivering modest successes in speech-to-text and speaker recognition technologies. Still, the ambition to apply AI to routine tasks or vital applications across the IC has been constrained by compliance concerns and the technology’s nascent stage. See more at 1983 AI Symposium Summary Report, CIA Records Search Tool (1983); Community Sponsored Plan for Artificial Intelligence, CIA Records Search Tool (1983); AI Symposium, CIA Records Search Tool (1983); Philip K. Eckman to John McMahon, Appreciation for Participation in AI Symposium, CIA Records Search Tool (1983); AI Steering Group: Meeting 4 Minutes, CIA Records Search Tool (1983); Proposal to Expand the Current APARS System, CIA Records Search Tool (1986); Philip K. Eckman to John McMahon, Intelligence Community Efforts Companion to Darpa Strategic Computing Program, CIA Records Search Tool (1984).

- Introducing ChatGPT, OpenAI (2022); GPT-4 Technical Report, OpenAI (2023).

- VC investment funding to U.S.-based generative AI companies between Jan 1, 2020 and July 12, 2023, SCSP Analysis via Pitchbook (July 2023).

- Generative AI Could Raise Global GDP by 7%, Goldman Sachs (2023).

- Final Report, National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence at 7 (2021).

- Anthony Vinci, The Coming Revolution in Intelligence Affairs: How Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems Will Transform Espionage, Foreign Affairs (2020); The Revolution in Intelligence Affairs: Future Strategic Environment, The National Academy of Sciences (2021); Anthony Vinci & Robert Cardillo, AI, Autonomous Systems and Espionage: The Coming Revolution in Intelligence Affairs, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (2021).

- The Office of the Director of National Intelligence defines open source intelligence (OSINT) as “intelligence produced from publicly available information that is collected, exploited, and disseminated in a timely manner to an appropriate audience for the purpose of addressing a specific intelligence requirement.” See more at U.S. National Intelligence: An Overview 2011, Office of the Director of National Intelligence at 54 (2011).

- Ben Nimmo, et al., Cross-Platform Spam Network Targeted Hong Kong Protests: “Spamouflage Dragon” Used Hijacked and Fake Accounts to Amplify Video Content, Graphika (2019).

- Ben Nimmo, et al., Spamouflage Goes to America: Pro-Chinese Inauthentic Network Debuts English-Language Video, Graphika (2020).

- Deepfake It Till You Make It: Pro-Chinese Actors Promote AI-Generated Video Footage of Fictitious People in Online Influence Operation, Graphika (2023).

- Deepfake It Till You Make It: Pro-Chinese Actors Promote AI-Generated Video Footage of Fictitious People in Online Influence Operation, Graphika (2023).

- Incident 486: AI Video-Making Tool Abused to Deploy Pro-China News on Social Media, AI Incident Database (2023).

- Ben Nimmo, et al., Second Quarter Adversarial Threat Report, Meta at 12 (2023).

- Steven T. Smith, et al., Automatic Detection of Influential Actors in Disinformation Networks, PNAS (2021).

- For example, Taiwan AI Labs uses a series of AI technologies to identify, analyze, and summarize suspected disinformation. See: Infodemic: Taiwan Disinformation Understanding for Pandemic, Taiwan AI Labs (last accessed 2023).

- Watermarking tools may include attaching green tokens to text outputs of LLMs, hiding an image or marker inside another image, or embedding identification tones within audio. See generally, John Kirchenbauer, et al., A Watermark for Large Language Models, arXiv (2023); Eric Hal Schwartz, Resemble AI Creates Synthetic Audio Watermark to Tag Deepfake Speech, voicebot.ai (2023).

- Content provenance verifies the source and version history of a given piece of media. The Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity’s (C2PA’s) technical specification is a leading example from industry. See Pawel Korus & Nasir Memon, Content Authentication for Neural Imaging Pipelines: End-to-end Optimization of Photo Provenance in Complex Distribution Channels, arXiv (2019); C2PA Technical Specification, Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (last accessed 2023).

- What is Blockchain Technology?, IBM (last accessed 2023).

- Security Policy for Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) Large Language Models (LLMs), General Services Administration (2023).

- The use of personally identifiable information (PII) by the Intelligence Community (IC) must adhere to the Privacy Act of 1974 (5 U.S.C. § 552a) and additional, disparate restrictions. Governing documents also include Executive Order 12333 (1981, 2003, 2004, 2008), and Intelligence Community Directive 503 (2008, 2015) by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. See more at 5 U.S.C. § 552a, Privacy Act of 1974; Executive Order 12333—United States Intelligence Activities, U.S. Federal Register (1981, 2003, 2004, 2008); Intelligence Community Directive 503: Intelligence Community Information Technology Systems Security Risk Management, Certification and Accreditation, Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2008, 2015).

- The General Services Administration issued an instructional letter (IL) to provide an interim policy for controlled access to generative AI large language models (LLMs) from the GSA network and government furnished equipment (GFE). The rule is valid until June 30, 2024. See more at Security Policy for Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) Large Language Models (LLMs), General Services Administration (2023).

- The IC Data Driven Future: Unlocking Mission Value and Insight, Office of the Director for National Intelligence (2023).

- Laura Dobberstein, Samsung Reportedly Leaked Its Own Secrets through ChatGPT, Situation Publishing (2023).

- Nicholas Carlini, et al., Extracting Training Data from Large Language Models, arXiv (2021); Nicholas Carlini, Privacy Considerations in Large Language Models, Google Research Blog (2020); Matt Burgess, ChatGPT Has a Big Privacy Problem, Wired (2023); GPT-4 Technical Report, OpenAI at 53 (2023).

- ODNI’s Office of Augmented Intelligence Mission (AIM) would be the most logical entity to act as the executive secretariat for the Committee.

- The ethics principles and the ethics framework are meant to guide the implementation of AI solutions in the IC. See more at Principles of Artificial Intelligence Ethics for the Intelligence Community, Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2020); Artificial Intelligence Ethics Framework for the Intelligence Community, Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2020).

- Corin R. Stone, The Integration of Artificial Intelligence in the Intelligence Community: Necessary Steps to Scale Efforts and Speed Progress, Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law at 18-21 (2021).

- IC Directive 203: Analytic Standards, Office of the Director of National Intelligence at 1 (2015).

- Industrial Strategy Building a Britain Fit for the Future, UK Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2017); Regulatory Sandbox Final Report: Onfido Limited (Onfido), Information Commissioner’s Office (2020).

- Yaniv Kubovich, Israeli Air Force Gets New Spy Plane, Considered the Most Advanced of Its Kind, Haaretz (2021); Anna Ahronheim, Israel’s Operation Against Hamas was the World’s First AI War, The Jerusalem Post Customer Service Center (2021).

- UAE National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence 2031, Government of the United Arab Emirates (2017); UAE Council for Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain, Government of the United Arab Emirates (2021); The Artificial Intelligence Program, Government of the United Arab Emirates (2020).

- New Robot Strategy, Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, Headquarters for Japan’s Economic Revitalization (2015); Impacts and risks of AI networking―issues for the realization of Wisdom Network Society, (WINS), Japanese Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Telecommunications Research Laboratory (2016); Fumio Shimpo, Japan’s Role in Establishing Standards for Artificial Intelligence Development, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (2017); Kosuke Takahashi, Japan to Outfit Kawasaki P-1 MPAs with AI Technology, Jane’s 360 (2019).

- AUKUS Fact Sheet, The White House (2022).

- Quad Critical and Emerging Technology Working Group, Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (2021); Husanjot Chahal, et al., Quad AI: Assessing AI-related Collaboration between the United States, Australia, India, and Japan, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (2022).

- Kiran A. Ahuja, Memorandum For Chief Human Capital Officers, Office of Personnel Management (2023).

- ICD 651, Performance Management for the Intelligence Community Civilian Workforce, Office of the Director for National Intelligence (2017); ICD 656, Performance Management System Requirements for IC Senior Civilians Officers, Office of the Director for National Intelligence (2012).

- Public Law No: 108-458, Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 § 1041(C).

- ICD 660, IC Civilian Joint Duty Program, Office of the Director for National Intelligence (2013); ICD 651, Performance Management System Requirements for the IC Civilian Workforce, Office of the Director for National Intelligence (2012); IC Standard (ICS) 660-02, Standard Civilian Joint Duty Application Procedures, Office of the Director for National Intelligence (2018).

- ICPM 2022-600-02, Intelligence Community Public-Private Talent Exchange, Office of the Director for National Intelligence (2022).

- 5 U.S.C. § 5105(a)(2), Introduction to the Position Classification Standards, (2009).

- 5 U.S.C. § 5105, Introduction to the Position Classification Standards, at 14 (2009).

- For more on AI Agents and similar systems, see Kyle A. Kilian, et al., Examining the Differential Risk from High-Level Artificial Intelligence and the Question of Control, Futures (2023).

- A Decadal Survey of the Social and Behavioral Sciences: A Research Agenda for Advancing Intelligence Analysis, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine at 6, 189–238, 312–315 (2019); Nick Hare & Peter Coghill, The Future of the Intelligence Analysis Task, Intelligence and National Security at 858–870 (2016); Efren R. Torres-Baches & Daniela Baches-Torres, Through the Cloak and Dagger Crystal Ball: Emerging Changes that will Drive Intelligence Analysis in the Next Decade, Journal of Mediterranean and Balkan Intelligence at 161- 186 (2017).

- Established under the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004. ICPM 2006-600-1 – National Intelligence Reserve Corps, Office of the Director for National Intelligence (2006).

- Final Report, National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence at 10 (2021).